Identity By Design

An investigation of Bristol’s remodelled ‘Centre’.

Nick Booth

Time and Meaning

Place identity, as a process for identifying historical and cultural meaning within a townscape, is increasingly recognized within Urban and Architectural Design as another aspect of drawing upon and developing the richness of the urban fabric. In “Identity by Design”, Bentley and Watson refer to the works of Aldo Rossi, who suggested that the Urban Designer act in part as an archeologist viewing the urban form as an artifact. They identify underlying historical patterns within the urban skeleton and the themes of the built form running through the fabric of the townscape, much like the tissue lying over the skeleton. By doing so, it is hoped that future development acknowledges the underlying context to create a sense of continuity of built form. Place identity goes further however by seeking also to identify the cultural meaning of the urban form. Recognising sets of meanings and how these are drawn on by members or groups of society as a way of forming their own perception of their roots, heritage, personal and social identity.

There is however an inherent danger! Urban development too rooted in the past may never allow a place to move forward? It must acknowledge that perception of identity is personal and may not correspond, or worse, fall in direct conflict with the cultural or historic perception of the surrounding townscape, and may lead to alienation and social exclusion. In other words, just whose culture is this? By way of an examination of these issues, it is considered that the recent redevelopment of an area known as “The Centre” in the City ofBristolprovides an interesting and note worthy case study. This shall be done through a brief investigation of its past, its realised form and its perceived success and failings within the scope of reflecting the social identity of the wider community.

‘The Centre’, Bristol

Ask any citizen of the city of Bristol in the South West of England for directions to ‘The Centre’, and it is likely that they will guide you to the same place. Most citizens of European cities, when asked, will be able to do the same, directing you to what they consider to be the physical, cultural or social centre from which different spokes of their city spring. Unusually however, Bristol’s ‘Centre’, on conventional street maps at least, does not formally exist. It stands as an area of open townscape between the commercial, civic and former industrial core of the city, yet does not form part of any of them. Despite being part of the historical townscape of the city since at least the 12th Century, it contains no major public building, has little in the way of a central point of focus and has played significantly different roles in the life of the city. It is even arguable that few Bristolians view it as anything that could be described as the ‘heart’ of the city or have even a simple fondness for the area. Yet all recognize it as ‘The Centre’ and its physical form stands at the very heart of the cultural and historical background of the city. So much so that when the City Council announced plans to remodel it in the early 1990’s, it become not only the subject of heated debate, but also shone a light on aspects of the cities past that had previously been quietly ignored. In doing so, it led not only to a questioning of what role the space should have, but also highlighted cultural divisions within the city and just what was being celebrated under the banner of civic pride.

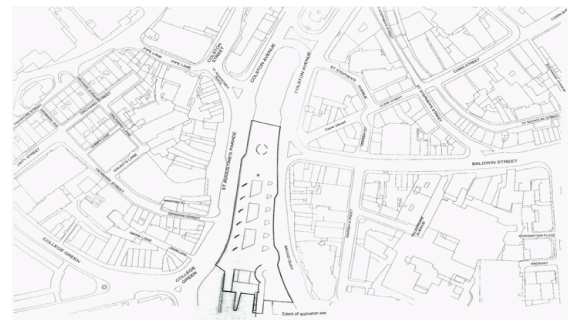

‘The Centre’, as it is popularly known, is an elongated strip of land running north to south some 360 metres in length, 70 metres wide. Divided into two parts, north and south, the northern part formed by Colston Avenue, the southern by St Augustine’s Parade on its western side; Broad Quay to the east. It is partially enclosed on three sides by a mixture of predominantly three and four storey buildings of relatively narrow plot widths, whilst the southern end forms a small quay onto one branch of Bristol’s Floating Harbour. To understand its unusual form, and to appreciate it’s relevance in the development of Bristol, one must examine the cities wider history.

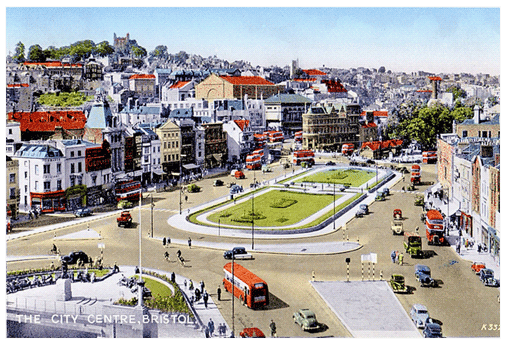

Fig 1. The Centre in context.

Historical Context

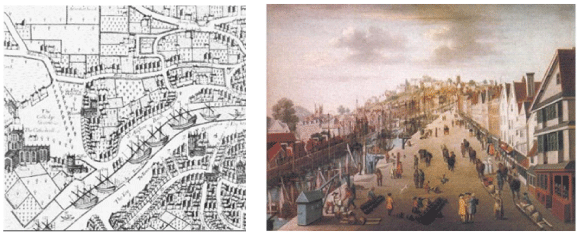

From its very beginnings, Bristol’s development was underpinned by the meeting of two rivers, the Frome and Avon, adjacent to a hilly outcrop rising above the Severn Estuary. From here access to the Estuary via the Avon was possible. It had already developed into an important local trading port by 1240 when identifying its potential for expansion, Henry II ordered a new channel be dug to divert the River Frome to the south. One of the biggest engineering schemes of the medieval age, St Augustine’s Reach allowed for new quays to be constructed large enough for ocean going vessels, leading to substantial new trade with France, North Africa and the Mediterranean. By the late 1300’s it had become England’s biggest port and by the mid 1600’s development in the form of business premises and lifting cranes had sprung up along both banks of the new channel. The Quay enabled ships to moor right in the heart of the town and in 1739, Alexander Pope described the scene: ‘in the middle of the street, as far as you can see, hundreds of ships, their Masts as thick as they can stand by one another, which is the oddest sight imaginable.” (Reproduced Foyle 2004 pg124). Behind these, large stone built warehouses were constructed. The financial area of Corn Street grew directly to the east of the harbour with Bristol Cathedral constructed close to the west bank.

Fig 2. Jacob Millerd’s map of 1673 Fig 3. St.Augustine’s Reach in the early 18th Century.

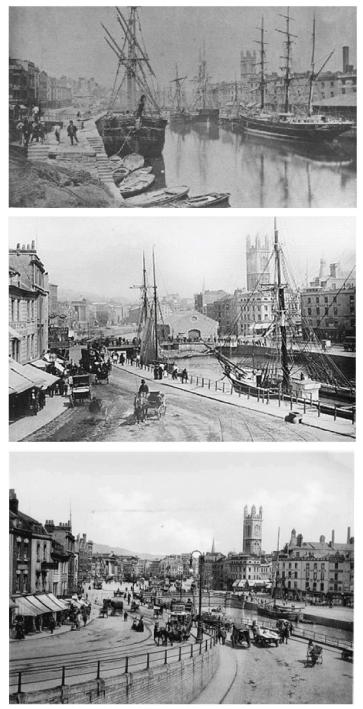

In 1712 a drawbridge across the harbour was constructed, which in turn was replaced by an iron swing bridge in 1868. By 1891 the pressure of cross town traffic and the decrease in the use of the Reach with the increase in boat size, led to the culvert of the harbor at its northern end, opposite Baldwin Street, creating Colston Avenue. In doing so, the space took on its second role, turning from quay to the cities transport hub.

Originally called the Tramway Centre, but quickly shortened by the populous to simply ‘The Centre’, it became a place of starting and terminating journeys as Trams bustled to and from the growing suburbs of Bristol. The clock of the Tram Company Headquarters on St Augustine’s Parade became a familiar and popular meeting place. Even so, just as the Coffee Houses and trading floors of Corn Street had been viewed as the ‘heart’ of 17th Century mercantile Bristol, up until World War II, it was undoubtedly the shopping centre around Wine Street and Castle Street to the north that was viewed as the focus of social life and ‘heart’ of the city, and not ‘The Centre’.

Fig 4, 5 & 6 in descending order – The Change from St Augustine’s Reach to The Centre – Images of the same view taken in 1860, 1882 and again in 1888.

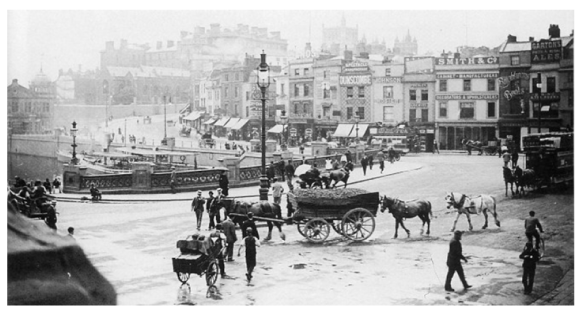

Fig 7. Above, St Augustine’s bridge looking up to College Green, 1892.

Fig 8, 9, 10 & 11 The growth of the ‘Centre” as a public Transport hub. From top left clockwise; New Tramway Centre 1908 with Ticket Office Clock; Looking up towards Baldwin Street, 1911; The busy Tramcentre,1925; Buses replace the trams but the iconic former ticket office clock remains, 1949.

Like many British cities, after the war, Bristol was determined to re-invent itself with a new urban framework. Whilst ‘The Centre’ had escaped the war relatively unharmed, work had already commenced to expand its role as a transport hub with further culvert work creating the southern part of ‘The Centre’ between 1937 and 1939. The tram system was dismantled and a new purpose bus station was built to the north in Lewins Mead to serve the new Shopping Centre of Broadmead. ‘The Centre’ became a major artery hub for routes into and out of the city and planting, flower displays and seating could not disguise the fact that by the early 1960’s, it had taken on its third role, that of a traffic roundabout. From this point on the noise and pollution associated with its role tended to exclude it from use by pedestrians other than as a space to move through quickly. It had little if any attraction as a public space in which to linger and it became associated with the gathering of people on the fringe of society. The role it had acquired was generally regarded negatively by the public and it was acknowledged that the space exerted a powerful influence on the public’s own perception of the city.

Fig 12. The newly completed ‘Centre’, with gardens and benches 1951.

Re-imagining the Past

In 1996, plans were produced for the remodelling and improvement of ‘The Centre’. The negative associations attached to it by the public were mirrored by wider concerns of the City Council as to the general identity and perception of Bristol from the outside world. The network of busy roads running through several of the primary townscape set pieces were seen as chocking the city, creating an unpleasant and outmoded environment, stuck in the transport planning of the post war years, and in doing so failing to reflect the desires of the City Council to portray Bristol as an attractive, regional capital, marketable within the growing global economy. Character was no longer created by necessity, but rather as a question of choice and it was recognised that a distinctive and attractive identity had an economic salience. At the same point, the City had also recognised the potential of waterside development following the closure of the Floating Harbour to commercial traffic in the 1970’s. As Meinig identifies in his paper ‘The Beholding Eye’, landscape can be viewed in many different ways, including as an opportunity to create ‘Wealth’. To exam landscape as a commodity, as holding a monetary value, or in the case of the Floating Harbour, as having a unique selling point. By the early 1990’s the Canon’s Marsh area to the south of ‘The Centre’ was already in the process of being converted to a site for arts, exhibition, entertainment, residential and office use. Therefore, the intention was that ‘The Centre’ act both as a public open space and as a high capacity but attractive gateway between the Habourside and the rest of the city centre. To re-link ‘The Centre’ back into the framework of the city and in doing so create a spatial sequence of open spaces.

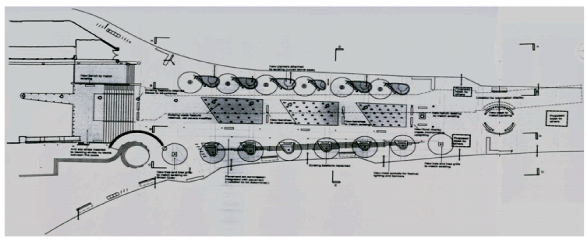

It would appear from the outset that the form of ‘The Centre’ was recognised as being what Rossi would classify as a primarily element of the local townscape. Its elongated length in comparison to its width directly related to its original use as a quayside. Similarly, the buildings fronting onto the space represented not grand formal buildings, but rather vernacular, commercial buildings. As such, they are what Amos Rapoport would consider in his book “House Form and Culture” as the unpretentious direct translation of the needs of the mercantile culture into physical form. The space therefore reflected its historic and cultural legacy, represented a symbolic function and held a deep rooted meaning in the life of the city. As such it was considered that its basic form should remain. There were however conflicting contextual issues; its historical association with the Floating Harbour; its context as a major transport hub and its role as a place of meeting, catching public transport and moving through from one part of the city to another. The desire was that all aspects be expressed and accommodated. The final implemented scheme designed by The Concept Planning Group changed, closed and resurfaced the roads running through the site, created a new linear water feature at the centre of a tree and seat lined promenade that led to steps and a water cascade down to the floating harbour, erected a series of illuminated beacons leading down to the waters edge and the provision of a new mast like structure.

Fig 14. Plan for the re-modelling of the Centre as submitted 1998.

From the outset it was desired to re-establish a symbolic and physical linkage with the historical role of water and the harbour. An alternative scheme for the re-opening of the culverted River Frome was rejected on the sensible grounds that this would interfere with movement across ‘The Centre’. Instead, the three shallow pools divided by broad wooden ‘bridges’ that form the linear water feature produced acts as the focus of the space. At its head is stands a Statue of Neptune, originally erected close to Bristol Bridge in 1772. Looking out across the water feature to the harbour, it is clearly intended to acts as both an accessible and prominent symbol of Bristol’s link with the sea. Within each of the pools, the water is moved by a succession of angled water jets that provide both a symbolic visual feature of the River Frome that feeds the dock, and creates the sound of rushing water that in part blocks out the sound of traffic. The water then cascades down a series of steps to the level of the floating harbour. This not only links the two bodies of water, but also provides direct access to the harbour where pontoons provide a landing stage for the local water ferry. It does not attempt to replicate the former dock, but does create a central water-based feature that encourages interaction, such as paddling, dipping ones fingers into the jets or splashing ones friends.

Fig 15. & 16. The Water Feature including directed jets, cascade steps and opportunity to paddle.

The act of procession produced by the pools is re-enforced by a series of ten, 6 metre high steel tubes known as the Millennium Beacons. Internally illuminated, their size is intended to reflect the scale of the space in which they sit. They are accompanied by a line of high backed seating, some of which contain bronze plaques celebrating prominent Bristolians who have links with the sea, and areas of planting, intended to reflect the formal planting displays within the former traffic roundabout. In addition, a line of semi-mature trees on both sides of the Promenade have been planted in order to create a stronger visual, physical and symbolic link between ‘The Centre’ and the Floating Harbour by mirroring a line of existing trees in both Narrow Quay to the south and Colston Avenue to the north. When viewing all of these elements along the north/south axis, these features create a strong visual sense of movement, as they stride in line down to the harbour. Unfortunately, most views of the space are experienced east to west as you cross the space, and in this context, along with the numerous lighting poles, they add to a somewhat random visual collection.

A more direct reference to Bristol’s nautical past and to the former role of ‘The Centre’ as its main quay has been erected to the north of the water feature. An octagonal mast and sail structure designed by Ferguson Mann, it clearly acts as a direct symbolic reference. Just as the medieval towers of Bologna became the city’s visual trademark, so perhaps for Bristol did the tall masts of the ships docked deep in the heart of the city. It has been deliberately positioned at the head of Baldwin Street, the location of the original crossing point of the harbour, and an axis of routes into ‘The Centre’. It is a punctuation point within the townscape, where the vista created by the linear route of the water feature down to the Floating Harbour and beyond is intended to be experienced from. From here, the markers lead the eye not only down to the intended harbour, but also to the far distant views of the Mendips and the countryside beyond, a subtle reminder that much of Bristol’s early wealth originated from the trade of agricultural goods produced in Somerset and Gloucestershire beyond the city walls. The mast and sail structure also provides the opportunity to display signs of upcoming events or advertisements for the civic bodies of the city, and acts very much like the old clock on the old Tram Centre Headquarters that stands nearby, as an identifiable landmark within the immediate townscape that acts as a place of rendezvous.

Figs 17. & 18. Neptune at the head of the water feature with its ‘Millennium Beacons’.

Fig 19. Neptune overlooking the water feature and beyond the Sail Structure.

Within the space, a pallet of materials are utilised with the intention of creating a smooth and safe surface across the space, whilst also clearly delineating between the vehicular and pedestrian routes, creating visual markers that act as routes across the space following traditional crossing points aligned with the principle routes into and out of ‘The Centre’, whilst also drawing reference from the facing materials and paving of the city docks and the surrounding townscape. Unfortunately, the high degree of mixed materials and the use of imprinted tarmac intended to resemble cobble stones creates a confused pattern to the surface, distracting from and failing to provide a much needed sense of continuity within the space.

Figs 20, 21 & 22 – Seating and planting, surface detail and bronze plaque.

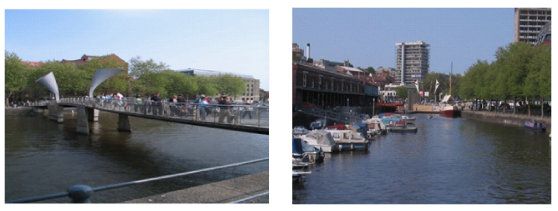

A new footbridge has been created across St Augustine’s Reach, creating a direct link between Queens Square and the new Millennium Square to the south of ‘The Centre’. The sculptural form of the counterweights have the appearance of horns, intended to refer to both nautical forms and to the use of fanfares in processions, in this instance, outward to the open ocean beyond. The foot way is decked in cast iron decks intended to reflect features found within the dockside area. The curvature of the foot way, the parapet and railings are all intended to be reminiscent of waves and the use of red lead paint below the foot way is used to pick up the colour used in shipping below the Plimsoll line.

Figs 23 & 24. Pero’s Bridge as views from St Augustine’s Reach towards Queens Square and the view from the bridge up towards the Centre.

It is clear therefore that the symbolism used is intended to link ‘The Centre’ to its former roles, in particular as part of the historic dock of Bristol. Monuments to the sea are placed on particular visually prominent positions, drawing the eye and the imagination to the water as representative of the ‘wide blue yonder’. The intention is to make cultural references to a perceived ‘golden age’ across variances of scale, from the form of ‘The Centre’ itself to the small ‘artifacts’, such as the bronze plaques and facing material. However, the issue of identity and the conceptualisation of history as a built form allows for design to become a social and politicised process. It can be argued that the desire for the new ‘Centre’ to reflect its past associations with the sea and trade also reflected the wider hopes and desired identity the Councillors wanted both for the city and to a degree with themselves. The sea represented the unexplored horizon, an untapped opportunity to explore and seek out new forms of trade. Just as Bristol’s medieval Merchant Venturers represented a band of confident and adventurous entrepreneurs, so the reinvigorated Bristol could shake off its past image and set sail into the global economy of the new millennium. In this way, ‘The Centre’ forms part of the pre-existing cultural landscape that acts both as an anchor and a springboard to both the remodelling of the city centre and to the desires of its leaders and its inhabitants.

Acknowledging the Past

Importantly, in celebrating and reflecting upon the Cities membership of this imagined new breed of Venturers; constructing a future based in part on association of the ‘golden age’ of Bristol’s past as the county’s port and second city; risked ignoring an important and uncomfortable aspect of its trading past; the prominence of Bristol within the Slave Trade.

The extent of Bristol’s involvement in the slave trade resonates in practically every civil and religious city landmark. Between 1698 and 1807, 2,114 ships set sail from Bristol to Africa and then on to plantations in the Americas, delivering over half a million slaves. It was from this large increase in trade and the massive tobacco, sugar, insurance and banking industries that supported it financed much of Bristol’s expansion at this time. Important parts of the city’s townscape such as Queen Square and Bristol’s Theater Royal were completed just as the city’s involvement reached its height in the mid 1700’s. It so dominated the financial base of Bristol at that time that it is calculated that most Bristolians were involved either directly or indirectly with the slave trade.

One such merchant and slave trader was Edward Colston, who until recently was widely viewed within the city as an inspirational figure. Having donated large sums of money to set up schools, hospitals and charitable organisations, his name permeates the city; Colston Hill,Colston Street,Colston Avenue and Colston Hall for example. In 1895 a statue of Colston was erected in commemoration of the merchant in the northern part of ‘The Centre’ on Colston Avenue where it still stands. In 1996, demonstrations were held after the city’s International Festival of the Sea failed to make any mention of slavery and in 1998, when information about in the slave trade became better known, the statue was vandalised, and Colston’s involvement in the slave trade became better known, the statue was vandalised, and internationally renowned Bristol band Massive Attack announced that it would never play Colston Hall. Debate ensued in the pages of local papers as to whether the Hall should be re-named or the statue be removed (neither of which has occurred). Whilst the new footbridge over St Augustine’s Reach has been named Pero’s Bridge after a slave who resided in the city, and a Slave Trail has been created, no official representative for Bristol has formally apologised for the city’s role in the slave trade and no permanent monument has been erected. The question can therefore be asked, if place identity and the re-appropriation of the city is done through the understanding that the historic city is the collective property of its inhabitants, can such a divisive past allow for all social and ethnic groups to share equally in the cultural landscape?

Figs 25 & 26 Edward Colston gazing down Colston Avenue towards the new Centre and The Bristol Theatre Royal.

It is clear that the renaming of streets or the taking down of statues can have the effect of sanitising history, and fails to allow issues to be discussed openly so as to actually inhibit the reconciliation process. It would appear however that despite utilising an ‘Inquiry by Design’ process, seeking out the views of interested parties, primarily conservation and business groups, and changing the design according to feedback, from the outset the Council failed to open up debate to black ethnic groups within the city, or attempt to understand their perceived role or sense of identity. Accordingly, it can be argued that what has been produced is not a ‘common vision’ but rather, by drawing on the morphological historical layers of ‘The Centre’, provides ideological material for only certain parts of the community. In doing so, it fails to reflect the role of the other communities or create a historic townscape in which all feel a sense of belonging or investment. Indeed, if one were cynical, it could be argued that it consciously ignored the past cultural suffering and that the intention to improve ‘The Centre’ stemmed principally from the Council’s desire to make the city more marketable. As such the space created aims only at simple interpretation of history required in order to stimulate the mind of a tourist. As Neil Leach suggests, place identity is in practice reduced to a mere commodity, “the essential complicity of the concept within the cultural conditions of late capitalism” (reproduced Bently/Watson 2007 pg11).

Even if one where to accept these criticisms, it is considered that the intention is not solely backward looking. It can be argued that by celebrating its entrepreneurial past, the remodeling of ‘The Centre’ suggests a sense of self belief. Rather than pay homage to privileged individuals or Royalty, the city is suggesting that both it’s past and future will be derived from the efforts of a community who share a set of common ambitions to succeed as a unified whole. The sense then is of a city looking forward rather than backward. Importantly, it has also been successful in bringing together previously fractured lines within the urban fabric. It has broken down its former separateness so as to create a far greater spatial and perceptual linkage between the centre and the surrounding areas. In doing so, it has created a coherent spatial sequence of both open and commercial spaces, each with its own identifiable sense of place.

Figs 27, 28, 29 & 30 The new linked open spaces. From top left clockwise, College Green, Millennium Square, The Centre and Queens Square.

As one moves through these spaces, it becomes apparent that each has become popular (though not exclusively so) with different sections of the community. College Green with teenagers,Queens Square with 20 something’s,Millennium Square for families with toddlers and ‘The Centre’ for a combination of all, if at a lower level. It has to a degree dispelled the noise of traffic in favour of the natural sound of water and seagulls, and in doing so provides connections to be made that are not restricted to cultural references. It has allowed these spaces to interact and become used by a far greater number of people, offering open potential for a wide range of different patterns of activity, for different communities to encounter each other and for new cultural interpretations to be inlaid. It is now the primary focus of Bristol’s night life and entertainment and whilst it may not have seen a level of revival to capture Bristol’s heart, it is now a much used public space.

Conclusions

The redevelopment of Bristol’s centre clearly shows the potential pitfalls of not acknowledging that the use of symbols rich in association derived from a pre-conceived perception of townscape, whilst reflecting values, ideals and aspirations of some parts of the community may also be counter productive. There is little now that can be fully labeled as tapping into a collective consciousness of culture. If focused only backward, it may not address the relevance of today or multiculturalism. The designer should therefore be sensitive to the perceptions of others, acknowledge that places or symbols can have multiple meanings and attempt to construct a form that allows the viewer to complete their own positive relationship to it.

Bibliography

Allinson, J (1995) Realising Visions: Development and Planning on City Centre Sites – A Case Study of Bristol. University of the West of England. Bristol:UWE Working Paper 40.

Bristol City Council Planning and Development Services (1998) Report to Planning, Transport and Development Committee Feb 1998 – St Augustine’s Reach.

Foyle, A (2004) Bristol. New Haven: Yale University Press

Meinig, D. W. (1979) “The Beholding Eye: Ten Versions of the Same Scene.” In The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays, edited by D. W. Meinig and John Brinckerhoff Jackson. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rapoport, Amos (1969) House Form and Culture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:Prentice-Hall

Watson, G B & Bentley I (2007) Identity by Design Oxford: Elsevier

Vanes, Jean (1977) The Port of Bristol in the Sixteenth Century. Bristol: Historical Association of Bristol University.

Internet based sources

St. Kitts-Nevis History Page (2002) The Bristol Slave Trade Walk. Retrieved on the 27 April 2007 from the World Wide Web. http://wesite.lineone.net/~stkittsnevis/bristol.htm.

Photographic and Graphic Record – Authors own unless indicted.

a) Figures 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and 13 – Memories of Bristol England Past and Present.Retrieved on the 25 April 2007 from the World Wide Web.http://www.bristolhistory.com/

b) Figures 1 and 14 – Photocopied extract form Planning File. Bristol City Council Planning and Development Services (1998)Report to Planning, Transport and Development Committee Feb 1998 – St Augustine’s Reach.

c) Figure 2 – Detail of Jacob Millerd’s Map. Foyle, A (2004) Bristol. New Haven: Yale University Press

d) Figure 3 – View of early 18th Century Bristol.Retrieved on the 25 April 2007 from the World Wide Web. http://www.cichw.net/pmodds1.html

e) Figure 25 – Statue of Edward Colston, Bristol. Retrieved on the 5 May 2007 from the World Wide Web. http://www.discoveringbristol.org.uk/